No products in the cart.

Interesting post at Ethan Hein’s blog – Repetition defines music – http://www.ethanhein.com/wp/2014/repetition-defines-music/

” Whether they come from jazz or classical, schooled musicians tend to equate quality with complexity, density and above all, unpredictability. This is a shame, since it gets in the way of our main job as musicians, which is to make people’s lives more bearable.”

Repetition defines music

Posted on by Ethan Hein

Musical repetition has become a repeating theme of this blog. Seems appropriate, right? This post looks at a wonderful article by Elizabeth Hellmuth Margulis, investigating the reasons why we love repetition in music in Aeon Magazine.

The simple act of repetition can serve as a quasi-magical agent of musicalisation. Instead of asking: ‘What is music?’ we might have an easier time asking: ‘What do we hear as music?’ And a remarkably large part of the answer appears to be: ‘I know it when I hear it again.’

Margulis is the first person I’ve seen advance the idea that repetition could be music’s most basic defining quality. I think she’s absolutely right.

Cultures all over the world make repetitive music. The ethnomusicologist Bruno Nettl at the University of Illinois counts repetitiveness among the few musical universals known to characterise music the world over. Hit songs on American radio often feature a chorus that plays several times, and people listen to these already repetitive songs many times. The musicologist David Huron at Ohio State University estimates that, during more than 90 per cent of the time spent listening to music, people are actually hearing passages that they’ve listened to before. The play counter in iTunes reveals just how frequently we listen to our favourite tracks. And if that’s not enough, tunes that get stuck in our heads seem to loop again and again. In short, repetition is a startlingly prevalent feature of music, real and imagined.

In fact, repetition is so powerfully linked with musicality that its application can dramatically transform apparently non-musical materials into song. The psychologist Diana Deutsch, at the University of California, San Diego, discovered a particularly powerful example – the speech-to-song illusion. The illusion begins with an ordinary spoken utterance, the sentence ‘The sounds as they appear to you are not only different from those that are really present, but they sometimes behave so strangely as to seem quite impossible.’ Next, one part of this utterance – just a few words – is looped several times. Finally, the original recording is represented in its entirety, as a spoken utterance. When the listener reaches the phrase that was looped, it seems as if the speaker has broken into song, Disney-style.

The speech-to-sound illusion, discovered by Diana Deutsch, UC San Diego. To experience the illusion, play the two recordings in sequence.

Credit: Diana Deutsch

Brian Eno: “Repetition is a form of change.”

The speech-to-song illusion reveals that the exact same sequence of sounds can seem either like speech or like music, depending only on whether it has been repeated. Repetition can actually shift your perceptual circuitry such that the segment of sound is heard as music: not thought about as similar to music, or contemplated in reference to music, but actually experienced as if the words were being sung.

This illusion demonstrates what it means to hear something musically. The ‘musicalisation’ shifts your attention from the meaning of the words to the contour of the passage (the patterns of high and low pitches) and its rhythms (the patterns of short and long durations), and even invites you to hum or tap along with it. In fact, part of what it means to listen to something musically is to participate imaginatively.

That is as good a definition of music as I’ve ever come across.

Can music exist without repetition? Well, music is not a natural object and composers are free to flout any tendency that it seems to exhibit. Indeed, over the past century, a number of composers expressly began to avoid repetitiveness in their work.

It should be no mystery that such music is (IMHO) uniformly godawful. This next bit is especially hilarious to me.

In a recent study at the Music Cognition lab, we played people samples of this sort of music, written by such renowned 20th-century composers as Luciano Berio and Elliott Carter. Unbeknownst to the participants, some of these samples had been digitally altered. Segments of these excerpts, chosen only for convenience and not for aesthetic effect, had been extracted and reinserted. These altered excerpts differed from the original excerpts only in that they featured repetition.

The altered excerpts should have been fairly cringeworthy; after all, the originals were written by some of the most celebrated composers of recent times, and the altered versions were spliced together without regard to aesthetic effect. But listeners in the study consistently rated the altered excerpts as more enjoyable, more interesting, and – most tellingly – more likely to have been composed by a human artist rather than randomly generated by a computer.

There’s so much here. I have never understood the prestige attached to Berio and Carter. Their music is plenty cringeworthyto begin with, and I’m not at all surprised to find that adding some repetition to it actually makes it more tolerable. People who don’t like electronic music accuse it of being “fake” and “unfeeling.” But this experiment proves that Elliott Carter can fail to convey emotions with pencil and paper just fine. Meanwhile, any halfway competent dance music producer can make people groove quite easily using a digitally looped samples and nothing else.

Repetition imbues sounds with meaning.

Repetition serves as a handprint of human intent. A phrase that might have sounded arbitrary the first time might come to sound purposefully shaped and communicative the second.

That phrase, “a handprint of human intent,” is a really good one. And how does repetition imbue sounds with meaning exactly?

Ask an indulgent friend to pick a word – lollipop, for example – and keep saying it to you for a couple minutes. You will gradually experience a curious detachment between the sounds and their meaning. This is the semantic satiation effect, documented more than 100 years ago. As the word’s meaning becomes less and less accessible, aspects of the sound become oddly salient – idiosyncrasies of pronunciation, the repetition of the letter l, the abrupt end of the last syllable, for example. The simple act of repetition makes a new way of listening possible, a more direct confrontation with the sensory attributes of the word itself.

This is another terrific potential definition of music: “Confrontation with the sensory attributes of sound.”

Anthropologists might feel that they are on familiar ground here, because it is now understood that rituals – by which I mean stereotyped sequences of actions, such as the ceremonial washing of a bowl – also harness the power of repetition to concentrate the mind on immediate sensory details rather than broader practicalities. In the case of the bowl-washing, for example, the repetition makes it clear that the washing gestures aren’t meant merely to serve a practical end, such as making the bowl clean, but should rather serve as a locus of attention in themselves.

[T]he repetition of gestures makes it harder and harder to resist imaginatively modelling them, feeling how it might be to move your own hand in the same way. This is precisely the way that repetition in music works to make the nuanced, expressive elements of the sound increasingly available, and to make a participatory tendency – a tendency to move or sing along – more irresistible.Even involuntary repetition, quite against our own musical preferences, is powerful. This is why music that we hate but that we’ve heard again and again can sometimes engage us unwillingly; why we can find ourselves on the bus enthusiastically grooving along until we realise that we’re actually listening to We Built This City by Starship.

And when we do want bits of speech to be tightly bound in this way – if we’re memorising a list of the presidents of the United States, for example – we might set it to music, and we might repeat it.

We’ve all unconsciously composed little melodies to help ourselves memorize something. You used to see it super commonly with phone numbers, back when people had to know phone numbers. In preliterate societies, music was probably one of the best methods for storing and conveying complex stories and information.

Margulis’ article is almost flawless, but I do want to take her to task on one assertion:

It’s also worth pointing out that there are many aspects of music not illuminated by repetition. It might be possible to transform speech into song, but a single bowed note on a violin can also sound unambiguously musical without any special assistance.

As a matter of fact, the musical nature of a single bowed note on a violin is further proof of the intrinsically repetitive nature of musical sound. Any pitched sound is really just a very fast rhythm. If you play a series of clicks and speed it up gradually, at around twenty clicks per second you stop hearing them as individual events, and instead experience them as a single stream, a phenomenon known as “event fusion.” Speed it up the click stream a little more and you begin to hear a distinct pitch. You can get concert A by playing 440 clicks per second. Your voice produces pitched sounds by rhythmically flapping your vocal folds. Here’s a video of what this looks like; be warned that it is not for the squeamish. Perceptually speaking, “pitch” is just our sensation of regular rhythms whose tempos are faster than the threshold for event fusion.

Margulis compounds her error further:

Repetition can’t explain why a minor chord sounds dark or a diminished chord sounds sinister.

This is where the explanatory power of rhythm shines brightest. If a single pitch is a very fast rhythm, then a chord is a very fast polyrhythm. A perfect fifth is three against two, also known as hemiola, which is a pretty elementary polyrhythm. The ratios of beats comprising minor and diminished chords are a lot more complex and difficult to parse, which in our culture we associate with darkness or evil.

Margulis is on firmer ground when she discusses the way that rhythm changes our passive hearing into active listening. Emphasis is mine:

[Repetition] captures sequencing circuitry that makes music feel like something you do rather than something you perceive. This sense of identification we have with music, of listening with it rather than to it, so definitional to what we think about as music, also owes a lot to repeated exposure.

Marc Sabatella says that we are all musicians. Some of us are listening musicians, and some are performing musicians. (And the performing musicians have to be listening musicians first and foremost.) Repetition turns us all into listening musicians.

The stunning prevalence of repetition in music all over the world is no accident. Music didn’t acquire the property of repetitiveness because it’s less sophisticated than speech, and the 347 times that iTunes says you have listened to your favourite album isn’t evidence of some pathological compulsion – it’s just a crucial part of how music works its magic. Repetitiveness actually gives rise to the kind of listening that we think of as musical. It carves out a familiar, rewarding path in our minds, allowing us at once to anticipate and participate in each phrase as we listen. That experience of being played by the music is what creates a sense of shared subjectivity with the sound, and – when we unplug our earbuds, anyway – with each other, a transcendent connection that lasts at least as long as a favourite song.

Needless to say, I found this to be an inspiring read. The comments are not as uniformly positive as you might think, however. A certain kind of intellectual musician gets really huffy when you suggest that they might find repetition comforting. One dude (I assume it’s a dude) even gets defensive about our propensity to enjoy sunsets. “They’re different every time! That’s what I’m enjoying.” The funniest comment is this one:

i FIND THIS ARTICLE CONTAINS THE TYPE OF INTELLECTUAL CRAP OF THE MUSICAL GUTTER AND IS AN INSULT TO THE INTELLIGENCE OF ANY PRACTICING MUSICIAN.

You can practically feeling the dude’s hands shaking from rage as he hits the Caps Lock. Why?

Why do highbrow musicians resist the loop?

People with a casual relationship to music tend to enjoy loop-based material, especially on the dance floor. But many if not most of the trained musicians I’ve worked with are resistant to the loop. Whether they come from jazz or classical, schooled musicians tend to equate quality with complexity, density and above all, unpredictability. This is a shame, since it gets in the way of our main job as musicians, which is to make people’s lives more bearable.

A few years ago I went to hear a highly respected quartet led by a saxophonist of whom the jazz nerds speak in hushed tones. I got to the club early enough to catch the sound check. While the sound guy fiddled with levels, the band played an open-ended funk groove on one chord. It was exhilarating: the loose interplay between the band members was anchored by the straightforward groove to make a satisfyingly tight sonic knot. I was all excited for the actual set, which turned out to be… a snooze. The material was full of startling key and time signature changes at unpredictable intervals. The band maneuvered through these sonic mazes proficiently, and I’m sure they enjoyed themselves, but for me it was like watching someone else play a difficult video game.

In America, our musical culture is a hybrid of mostly western European, African and Caribbean traditions. Our musical ancestors have some philosophical differences around repetition. The western European classical music term for a continually repeated phrase is an ostinato, from the Italian word for “stubborn.” It’s related to the English word obstinate. This is not an attractive quality in a person and the European classical world doesn’t think too highly of it as a quality of music either. Theodor Adorno criticized the repetitiveness of popular music as being “psychotic and infantile.” He wasoutspokenly contemptuous of jazz and dance music generally. From his book Prisms:

Considered as a whole, the perennial sameness of jazz consists not in a basic organization of the material within which the imagination can roam freely and without inhabitation, as within an articulate language, but rather in the utilization of certain well-defined tricks, formulas, and cliches to the exclusion of everything else.

Adorno is factually correct. But he’s wrong that this is a defect of the music. The tricks, formulas and cliches are the basic grammar of pleasure. Cooking tofu with sesame oil, ginger and soy sauce is a cliche too, and for good reason, it consistently makes the tofu taste good.

Fortunately, we in America are blessed with the strong African and Caribbean influences, and the musicians of these cultures hold circularity as a high virtue. To pick one example out of a vast many, Fela Kuti’s “Beasts Of No Nation” repeats the chords G minor to F for about half an hour. It doesn’t get old.

Sample-based hip-hop is the music most exciting my ears right now. The best beatmakers find fragments that were part of a linear stream and bend them into unexpected loops.

I don’t know the provenance of this RZA quote beyond Wikipedia, but it’s a good one:

For hip hop, the main thing is to have a good trained ear, to hear the most obscure loop or sound or rhythm inside of a song. If you can hear the obscureness of it, and capture that and loop it at the right tempo, you’re going to have some nice music man, you’re going to have a nice hip hop track.

This is good advice for any musician, not just hip-hop beatmakers.

Why isn’t repetitive music boring to listen to?

Once we’ve grasped the pattern, why don’t we get bored listening to repetitive music? The best answer I’ve found is in Matthew Butterfield’s paper, The Power of Anacrusis: Engendered Feeling in Groove-Based Musics. Butterfield argues that we don’t hear each repetition as an instance of mechanical reproduction. Instead, we experience the groove as a process, with each iteration creating suspense. We’re constantly asking ourselves: “Will this time through the pattern lead to another repetition, or will there be a break in the pattern?”

Butterfield describes a groove as a present that is “continually being created anew.” Each repetition gains particularity from our memory of the immediate past and our expectations for the future.

Why isn’t repetitive music boring to play?

Quora user Andrew Stein asks:

Musicians: How do you deal with playing songs that have very monotonous parts?

I’m going to use James Brown’s Sex Machine as an example. Don’t get me wrong, I love the song. However, the rhythm guitar seems to be nothing but 2 chords played over and over and over with no variation (except for the bridge). What is it like to have to play songs like that? Even if you like the song, do you dread it, or do you just have fun as long as you are playing music? If you are bored, how do you deal with it? Does your mind wander while you play, or do you have to concentrate?

This is actually quite a profound question. It gets to the heart of the major conflict playing out in western music right now between linearity and circularity.

Western classical music of the common-practice era usually takes the form of a linear narrative, a hero’s journey. Music from Africa (and many other places) tends to take the form of cycles, setting a mood rather than telling a story. This is a gross oversimplification, but I think it’s an extremely useful one.

The major musical event of the past hundred years (in western cultures anyway) has been the hybridization between European linearity and African (and Latin American and Asian) circularity. This has been most dramatic in the United States, with its enormous populations of immigrants and descendants of slaves. Our popular music has been getting more and more circular (more “African”) with every passing decade, from jazz to R&B to rock to funk to hip-hop. And our popular music makes its presence felt in every corner of the world.

James Brown is a critical figure in this story because he did his best work at a time when black Americans were beginning to assert pride in their roots and ethnic identity. (“Say it loud, I’m black and I’m proud!”) JB made it an explicit goal to push his music into a more African direction: complex rhythmic grooves, minimal harmonic activity, improvisational chants instead of sung melodies, trance-like repetition over long time scales. “Sex Machine” isn’t even his most repetitive groove. Check out “There Was A Time,” a four-bar cell repeated more or less identically for over seven minutes. And by the way, JB’s love of Africa was reciprocated; he influenced a generation of African musicians, most famously Fela Kuti.

So, to answer Stein’s question: If you approach “Sex Machine” with a western classical value system, it certainly is going to seem “monotonous.” You may well enjoy the song, but you’d naturally imagine that it’s intellectually unsatisfying and therefore boring to play.

Coming at “Sex Machine” from an Afrocentric perspective is quite different. The groove is so devastating, so effortless, so transporting, that adding variations to make it more narrative or “interesting” would only water it down and diminish its power. The groove isn’t really aimed at your prefrontal cortex. It’s aimed at the rest of your brain, your limbic system and motor cortex, not to mention your entire self from the neck down. The point of funk is to dissolve your conscious self into the holistic unity of the groove. As James Brown says in “Give It Up Or Turnit A-loose,” “Check out your mind, swing on the vine, in the jungle brother.” And as Prince sings, “There’s joy in repetition, there’s joy in repetition, there’s joy in repetition,there’s joy in repetition.”

Playing a James Brown groove is much harder than it seems. Learning the riff is easy enough, but sustaining it at length takes Jedi-like focus. Playing funk well demands a certain relaxed intensity, and if that sounds like an inherent contradiction, it is. Sustaining the balance between looseness and discipline takes more than musical skill; it requires you to be able to suspend your anxieties, your distracting thoughts and your self-consciousness. Fortunately, the groove itself is a great tool to help you do exactly that. As Kofi Agawu says:

Repetition enables and stabilizes; it facilitates adventure while guaranteeing, not the outcomes as such, but the meaningfulness of adventure. If repetition of a harmonic progression seventy-five times can keep listeners and dancers interested, then there is a power to repetition that suggests not mindlessness or a false sense of security (as some critics have proposed) but a fascination with grounded musical adventures. Repetition, in short, is the lifeblood of music.

When you listen to repetitive music, time is progressing in its usual linear way, but the cyclic sounds evoke timelessness and eternity. Victoria Malawey describes harmonic ostinati as having a feeling of alternating repose and tension. I’ve found this to be true of looped samples as well; the first and third repetitions will have a “call” feeling that is “answered” by repetitions two and four. The continuing reversal of call and response, of front and back halves of a phrase, can evoke other image schemas as well. Malawey lists swinging, fluttering, quivering, jiggling, hovering and flickering as appropriate image schemas for repetitive music.

Repetition and recording

Recorded music makes it possible for us to effortlessly and endlessly repeat segments of music ranging in length from short phrases to entire artists’ catalogs. Not only do we love to listen to repetitive songs, we love to do so repeatedly. In Capturing Sound, Mark Katz points out that recording makes it possible to have precisely repeated listening experiences for the first time in history.

Live performances are unique, while recordings are repeatable… [A]ny orchestra can play Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony many times; each performance, however, will necessarily be different.

Such repeated listening can’t help but change our relationship to the art form of music in general.

For listeners, repetition raises expectations. This is true in live performance; once we’ve heard Beethoven’s Fifth in concert, we assume it will start with the same famous four notes the next time we hear it. But with recordings, we can also come to expect features that are unique to a particular performance—that a certain note will be out of tune, say. With sufficient repetition, listeners may normalize interpretive features of a performance or even mistakes, regarding them as integral not only to the performance but to the music. In other words, listeners may come to think of an interpretation as the work itself.

The repeatability of recorded sound has affected listeners’ expectations on a much broader scope as well. When the phonograph was invented, the goal for any recording was to simulate a live performance, to approach reality as closely as possible. Over the decades, expectations have changed. For many—perhaps most—listeners, music is now primarily a technologically mediated experience. Concerts must therefore live up to recordings. Given that live music had for millennia been the only type of music, it is amazing to see how quickly it has been supplanted as model and ideal.

While we usually think of listening to recordings as a passive act compared to playing an instrument, Margulis is making me rethink that assumption. Maybe I’m doing more and more active imaginative participation in a song as I do my fiftieth or sixtieth or seventieth listen.

Repetition and music education

The possibilities of repeated listening to recordings also has profound implications for music education. Cognitive scientists use the word “rehearsal” to describe the process by which the brain learns through repeated exposure to the same stimulus. As they like to say, neurons that fire together wire together. Repetitive music builds rehearsal in, making it more accessible and inclusive. Kirt Saville draws this connection in his paper, Strategies for Using Repetition as a Powerful Teaching Tool.When a student brings a recorded song to me that they want to learn, the first thing I do is load it into Ableton and mark off the different sections with a simple color-coding scheme: blue for verses, green for choruses, orange for instrumental breaks and so on. This enables even non-readers to grasp the overall structure of the song. I then loop a short segment, usually significantly slowed, and have the student repeat it until they’ve attained some proficiency with it. As the student progresses, the loops get longer until they encompass entire sections. If a particular phrase is especially troublesome, I can send the student home with an mp3 of that phrase looped endlessly to practice over.

I can’t overstate the value of using loops of actual songs played by actual musicians, as opposed to metronomes or fake-sounding MIDI tracks. The metronome demoralizes students quickly, and convenient though MIDI is, it doesn’t convey feeling and nuance. Study of the genuine article, with its groove and feeling intact, is a vastly richer and more engaging experience. Also, listening to music loops creates a trance-like, meditative feeling, as fans of repetitive electronic dance music will attest. This meditative state is most conducive to flow, and turns repeated drilling into a pleasurable act.

Repetition is fundamental to all forms of human learning, as the rehearsal of the material causes repeated firings of certain networks of neurons, strengthening their connections until a persistent pattern is firmly wired in place. Young children enjoy the endless repetition of any new word or idea, but for older children and adults, such literal repetition becomes tiresome quickly. Still, rehearsal remains a critical memorization method, especially in the intersection of music and memory. The trick for a successful music instructor is to lead the students through enough repetition to make the ideas stick, without descending into tedious drilling.

The key to effective music learning is “chunking,” breaking a long piece into short, tractable segments. Depending on the level of the students, those chunks might be quite short, a single measure or phrase. Once a series of chunks is mastered, they can be combined into a larger chunk, that can then be combined with still larger chunks until the full piece is mastered. Chunking helps get students to musical-sounding results quickly. Rather than struggling painfully through a long passage, the student can attain mastery over a shorter one, which builds confidence. Furthermore, Saville points out that chunking can help make feedback more immediate and thus more effective:

Experienced music teachers become adept at chunking and sequencing the reassembly of difficult musical passages as a means of solving complex performance problems. By chunking, we eliminate the delayed feedback inherent in a long list of items to be fixed after the performance of a long passage and instead focus on more useful and immediate feedback. Repeating the two most critical measures of a sixteen-measure phrase will solve more problems than the repetition of the entire phrase. Likewise, chunking the three troublesome interval leaps in a four-measure phrase will increase rehearsal efficiency and productivity.

Saville cites the music educator’s truism that “accurate feedback may be the single greatest variable for improving learning.” The longer the delay between the performance and the feedback, the less effective it is. It’s best to give feedback in the moment, immediately after looping a passage, or even better, while the loop is in progress.

Repetitive drilling demoralizes students quickly. The challenge is to find a way to get students to repeat new ideas enough times to master them without boring them to the point of discouraging them. The strategies Saville lists are intended for classical ensemble teaching, but they’re equally valid for jazz, rock, country and pop. Some of his recommended methods include:

- Call-and-Response Repetition — the teacher leads by example, without explaining the how or why, and students must use their own ingenuity to imitate.

- Performer-Switching Repetition — repeating a phrase with different students playing on each pass.

- Guided Discovery with Repetition — asking students to describe what they’re doing.

- Repetition with Addition or Subtraction of Degrees of Freedom — for example, having students perform the rhythm of a passage on a single pitch. I call this exercise the one-note groove and find it very valuable.

Looping, fractals and recursion

Margulis’ article got me thinking about how music contains many different levels of repetition: at the microsecond level, the beat level, the phrase level, the section level, the song level and on upwards. Music is full of fractal recursion.

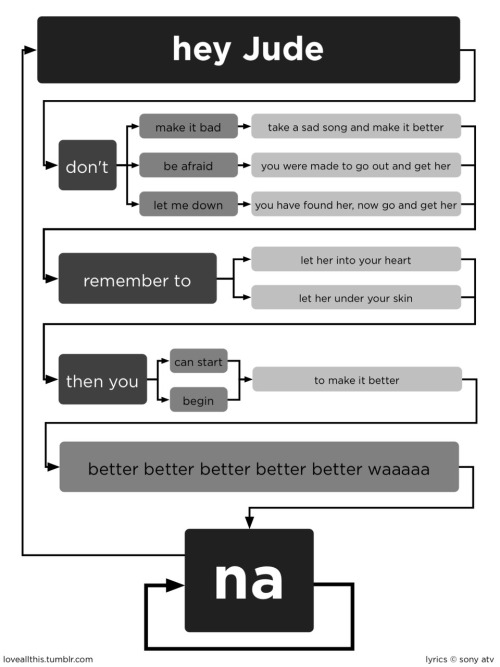

Nearly all world music uses repeating phrases grouped into longer phrases, and groups those metaphrases into meta-metaphrases. Entire sections get repeated to form still higher level structures. For my ears, the most satisfying music is the most modular and recursive. The joy of moving between different levels of recursive loops is one of the purest pleasures I know. The Beatles’ “Hey Jude” is a perfect case in point.

By the time you get to the “Na na na na” part, of “Hey Jude,” you’re ready to hear that short nonsensical phrase loop as many times as the Beatles see fit to deliver it to you. It repeats for over half the song’s overall length, and could probably continue for another forty-five minutes as far as I’m concerned.

I’ll close with a Prince quote I’ve already used here, and in many other places on this blog. It feels appropriate to repeat it:

There’s joy in repetition

There’s joy in repetition

There’s joy in repetition

There’s joy in repetition

Words to live by. Words to live by. Words to live by. Words to live by